“The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge, but fools despise wisdom and instruction” (Proverbs 1:7). The fact that knowledge begins with God and that everyone has some degree of knowledge can be used in apologetics to expose the unbeliever’s suppressed knowledge of God. The argument is powerful and irrefutable. But what exactly is knowledge? Does knowledge really begin with God, or does it begin with self? How do human beings attain knowledge? What is the relationship between knowledge and truth? Philosophers debate these issues, but does the Bible have anything to say about this subject?

What is Knowledge?

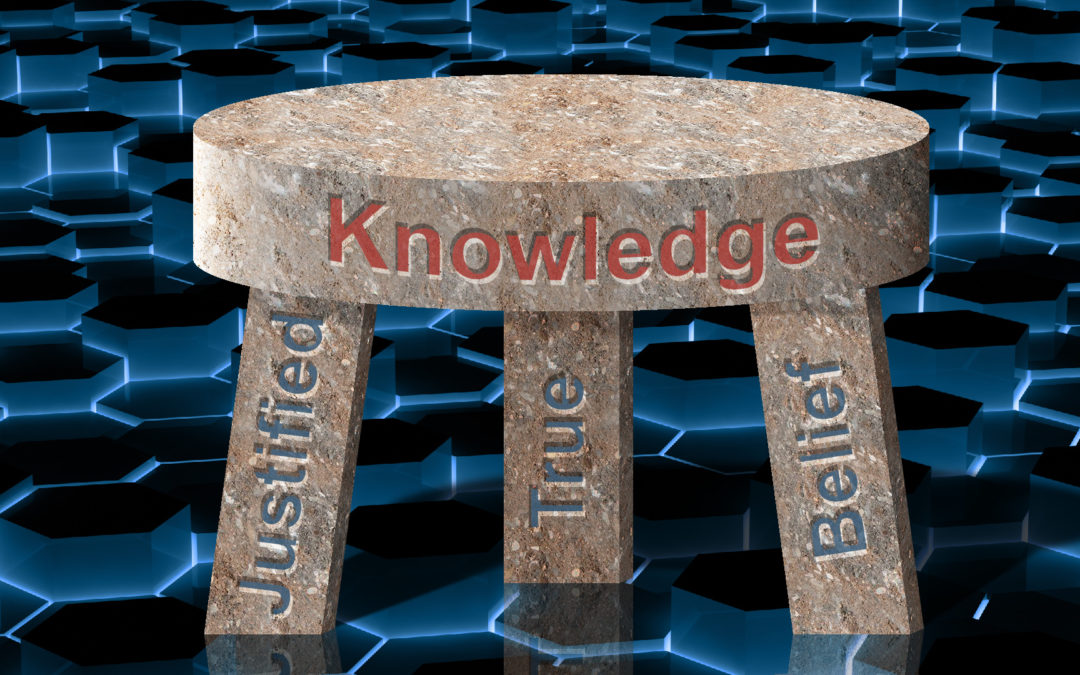

The study of knowledge and how we know what we know is called epistemology. People know lots of things. But what exactly is knowledge and how does it relate to truth? Suppose Kelly says, “ I know the Pacific Ocean is larger than the Atlantic Ocean.” In saying this, Kelly is affirming something. First, her opinion regarding the claim is positive. She believes that it is indeed the case that the Pacific Ocean is larger than the Atlantic. So knowledge is a type of belief – a positive mental attitude toward a proposition.

But knowledge is much more than this. The belief must also be true. Suppose Jacob said, “Actually, I know that the Atlantic Ocean is larger than the Pacific.” Jacob may well believe this, but the statement is false. Jacob’s belief does not correspond with reality, and therefore it is not actually knowledge. Knowledge must be a true belief. But there is more to it than that. In order for a true belief to count as knowledge, it must be justified; there must be a good reason (or several good reasons) for the person to believe it. So when Kelly makes her claim about the Pacific Ocean, she has implied that her belief is true and that she has good reasons to believe it. We can illustrate this with the following example:

Suppose Pam says, “I just know it will be sunny at the church picnic next week.” Suppose that when the day of the picnic finally comes, it is indeed sunny. Pam says, “I knew it all along!” But did Pam really know that it would be sunny? No. She had a belief, and it was a true belief. But she really didn’t have any good reason to believe it. A day after the picnic, Pam could correctly say, “I know it was sunny yesterday at the picnic” because her true belief now has a good reason behind it. Namely, Pam’s memory of the event serves as the justification for her true belief. Knowledge is true, justified belief.[1]

What is Truth?

“Jesus answered, ‘You say correctly that I am a king. For this I have been born, and for this I have come into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who is of the truth hears My voice.’ Pilate said to Him, ‘What is truth?’” (John 18:37b-38a).

It may surprise many to learn that secular philosophers disagree on what the definition of “truth” should be. Some would define truth as “in accordance with reality,” or “the actual state of things.”[2] While this is accurate, it is not sufficient as a definition to allow us to distinguish truth from error because how do we define “reality” or “the actual state of things?” These are perhaps synonyms for ‘truth’ which makes the definition circular and not useful for us to quantitatively distinguish truth from error. Is there a (precising) definition that is non-circular? As is often the case, the Bible has the answer.

“Jesus said to him, ‘I am the way, and the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father but through Me’” (John 14:6). “’Sanctify them in the truth; Your word is truth’” (John 17:17). In these passages, Jesus identifies Himself as the truth, and also God’s Word as truth. Those may seem like two different standards for truth until we recognize that Jesus is the Word (John 1:1, 14). The Greek word translated “word” in these passages is “logos” which means the expression, utterance, or voice of a conception or idea. This goes beyond and yet is consistent with our English definition of “word” since we indeed use words to express the conceptions of our mind. The Logos (Word) of God is the expression of His mind. And since Jesus identifies God’s Logos as truth we have a non-circular, biblically-based definition of truth: truth is that which corresponds to the mind of God.

This applies to the person of Jesus who, as God, corresponds perfectly to the mind of God. So Jesus rightly says that He is the truth. But it also applies to propositional (written or spoken) truth, such as God’s written Word which corresponds perfectly to His mind since He wrote it. Truth is not only those things spoken by God, but anything that corresponds to God’s mind. Something is true if it is something that God would say. Anything that God affirms or would agree with is true.

This definition of truth is no doubt bothersome to those with a secular worldview. Those unbelievers who allow for the existence of a god of some sort generally prefer a god with the same limitations that we humans have. We tend to think of truth as an independent entity of the universe that we discover using our minds and sensory organs. And in our sin nature, we tend to think that God’s mind is like ours and that He also discovers truth this way, albeit much better than we do. But the Bible indicates that this view is mistaken. Although we are made in God’s image and therefore can reflect God’s thinking in some ways, we would do well to remember that God’s mind is fundamentally different from ours because He is the Creator.

God’s mind determines all truth. Our minds discover some truth. As Creator, God is completely sovereign over the universe. So, whatever God affirms in His mind determines reality. As creatures, our minds have been designed by God to receive some of the truth that His mind determines. The act of our mind receiving truth from God is called “revelation.” God reveals Himself when He gives us knowledge. But what is the mechanism?

Revelation

Truth is that which corresponds to the mind of God. But unbelievers sometimes scoff at this definition and attempt to refute it by asking, “How can you possibly know what God thinks?” But, of course, this question is easy to answer: revelation. God has revealed some of His thoughts to us and He has done this in numerous ways. Most specifically, God used men to write a book that expresses His thoughts, namely, the Bible. Do you want to know what God thinks about something? Read the Bible!

But there are other ways God has revealed Himself. God has placed knowledge into the core of our being from our conception. For example, God’s moral requirements – His laws – have been placed into the minds of all people. Thus, even people who have never read the Bible have some knowledge of the law of God (Romans 2:14-15). We are able to have some knowledge of right and wrong even without reading the Bible because God has “written” His law on the hearts of all people. This is a type of revelation.

God has designed sensory organs, such as eyes and ears, that allow us to have knowledge of the external world. Furthermore, God has placed knowledge within us that our senses are basically reliable; so, we can have confidence that what we see and hear is a good map of reality. By our senses, we can learn true things about the world, such as “the sun is very bright.” Consider the contrary. If God had not designed our senses to be basically reliable, or if God had not given us knowledge that our senses are basically reliable, then we could never learn anything about the external world. Sure, we might see that the sun is bright. But we would have no reason to trust that what we see corresponds to the real universe.

God has also placed some knowledge of logic within us. Logic is the principles of correct reasoning – a reflection of the way God thinks. God created mankind after His image/likeness. And this includes the ability to think – to some extent – in a way that is consistent with God’s character. Thus, we are born with some degree of rationality. (It is possible to prove that some laws of logic are known without ever being learned; hence God has “hardwired” them into our being.)[3] Furthermore, God has given us the ability to improve our reasoning skills through careful contemplation using our mind and from education using our sensory organs.

In addition, God has placed some knowledge of Himself inside all people such that when we look at the natural world, we instantly recognize it as the work of God. Romans 1:19-20 states, “because that which is known about God is evident within them; for God made it evident to them. For since the creation of the world His invisible attributes, His eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly seen, being understood through what has been made, so that they are without excuse.” Thus, all people have knowledge of God.

This fact should have a profound impact on the way we do apologetics. If indeed all people have knowledge of God, then they do not require additional evidence for God. Many Christians proceed as if the unbeliever is genuinely ignorant of God. Under this mistaken belief, the Christian urges the unbeliever to trust in God by presenting new evidence for God. But according to Romans 1:18-20, all unbelievers already know God but they “suppress the truth in unrighteousness.” The presuppositional apologist therefore aims to expose the unbelievers suppressed knowledge of God.

Since all knowledge is ultimately from God, it follows that anything we know has been revealed to us by God in some way. We can know things by sensory experience, but only because God designed our senses to be basically reliable. We can know things through rational reasoning, but only because God designed our minds and has given us access to His laws of logic. Hence, the biblical God is the ultimate justification for all truth claims.

Of course, even people who have never read the Bible do have knowledge. But this is because the Bible is true. Unbelievers learn things through sensory experience and rational reasoning just like believers. But in order for their beliefs to be justified, they would require some reason to trust their sensory organs, and their thinking process. If the Bible were not true, there would be no reason to trust in such things.[4] Hence, all beliefs based on those assumptions would lack justification.

We can have knowledge only because God exists and has revealed Himself in exactly the way the Bible teaches. God, as revealed in the Bible, is the ultimate foundation for all human knowledge. If the Bible were not true, we could know nothing. We might have beliefs, and some of them might even be true, but they could never be justified apart from the biblical worldview.

Logical Primacy vs. Chronological Discovery

Many beliefs are justified only after the fact. This confuses some people, and an example may clarify. We must believe that our sensory organs are basically reliable in order for us to have confidence in anything we read. When we then read the Bible, we can see that our confidence in our sensory organs was justified because God created them. The truth of the Bible is logically more foundational than the truth that our senses are basically reliable because the former justifies the latter. However, we discover the truth in the pages of Scripture (that God designed our senses) after we have already trusted our senses. Our belief in reliable senses is chronologically first, but the biblical truth that God designed our senses to be basically reliable is logically primary.

By analogy, suppose you are driving up a hill. As you reach the top, you see a house on the other side of the hill. The first thing you see is the roof because the lower portions of the house are still obscured by the hill. As you continue to round the top of the hill and descend, you then see the top story of the house, and finally the lower level as the house becomes visible. You never actually see the foundation of the house, but you suppose it is there since all houses require a foundation. So the order in which you discover the sections of the house is: roof, second story, first story, foundation.

But this is not the order in which the house was built. A roof cannot exist without the supporting walls of the second story, which cannot stand apart from the first story, which cannot stand without the foundation. Obviously, the foundation was laid first, then the first story was built upon it, and the second story upon the first. The last thing to be constructed would be the roof because it logically requires all the other structures to be already in place. So the logical order in which the building was constructed was the opposite of the chronological order in which we become aware of the building.

Likewise, there can be no doubt that human beings are aware of self and their sensory experiences long before they read in the Bible the justification for those things. Yet, the truth of the Bible is logically prior to sensory experience, since our sensory experiences are only ultimately justified by appealing to the God of Scripture. Many well-meaning Christians argue against the presuppositional apologetic due to this misunderstanding. They argue (contrary to Proverbs 1:7) that knowledge begins with self, not with God. But God is logically prior to all our knowledge of anything, and apart from His revelation we could know absolutely nothing.

For an example of how the Christian worldview alone justifies knowledge, see the article “Are You Epistemologically Self-Conscious?”

[1] Some philosophers do not entirely agree with this definition, however most agree that knowledge is at least true justified belief. Some would argue that additional qualifiers are also required, such as certainty. These nuances are not necessary for our discussion.

[2] This is called the correspondence theory of truth.

[3] One example of this is modus ponens. This law of logic cannot be proved without using it. Hence, you can never learn it unless you already know it. Yet, people do know modus ponens. Therefore, they must have been created already knowing it.

[4] Unbelievers often try to justify their senses by appealing to their senses. They would claim to know that their eyes are reliable by appealing to the sense of touch. “When I feel the thing I’m looking at, it matches.” But this assumes that their sense of touch is reliable. How do they know that? Perhaps they would appeal to their sight. But they have justified their sight by their sense of touch, and their sense of touch by their sight. This is known as a vicious circular argument: claim A depends on claim B which depends on claim A. Both claims are ultimately unjustified.