What is presuppositional apologetics? The word ‘apologetics’ refers to giving a rational defense of the faith – in this case, the Christian Faith.[1] It is a way of demonstrating that Christianity is true, and refuting allegations to the contrary. The importance of apologetics can hardly be overstated. We live in an age of rampant skepticism against Scripture, and naïve acceptance of secularism. If we are to obey Christ’s command to make disciples of all nations (Matthew 28:18-20), we need to be ready to defend the faith against its accusers.

But how should we defend the faith? What method should we use? Christians disagree on the answers to these questions. However, there are several basic schools of thought on apologetics. Three of the most common are the “classical” approach, the “evidential” approach, and the “presuppositional” approach. Each of these methods will give a different answer to the question, “How do we know that the Bible is true?” How you answer that question will reveal your apologetic method.

Apologetic Methods

Some Christians might simply answer the question with “We don’t know that the Bible is true. It’s unprovable. But we accept it by faith.” This belief is called fideism. In this view, the Bible cannot be established to be true by rational reasons, and it doesn’t need to be. We are obligated to accept the Bible as true by “blind” faith without rational reasons. It may sound very pious, but fideism is contrary to Scripture. The Bible tells us that we are to be ready to give a rational defense (an “apologetic” from the Greek word “apologia”) to everyone who asks us about our faith (1 Peter 3:15). It is impossible to give a rational defense of the faith if you believe that we have no rational reason to believe it. Fideism is not an apologetic method, but the abandonment of apologetics, and is therefore contrary to Scripture.

Evidentialism and the classical method of apologetics are similar in many respects. Their essential commonality is that the mind of man is able on its own through reason and observation of evidence to correctly conclude that the Bible is true, or is at least very likely to be true. Man’s reasoning and man’s understanding of evidence are the standards by which the Bible is judged to be true. Under these methods, the Christian encourages the unbeliever to use his mind and senses to examine the evidence from nature, history, etc. and to conclude that the Christian worldview is very probably true.

There are distinctions between evidentialism and the classical approach. Evidentialism is primarily inductive (though it does use deduction as well). That is, it encourages the unbeliever to form a general conclusion from many specific instances. For example, an evidentialist might encourage an unbeliever to consider miracles as evidence for Christianity. After all, everyday experience shows that people generally don’t rise from the dead, that the blind do not normally receive sight, that the lame do not normally walk. Therefore, it is very likely that the miracles recorded in Scripture go beyond natural law and must be supernatural.

Being primarily inductive, the evidentialist method is necessarily probabilistic. When forming a general conclusion from specific instances, you can never be sure that the generalization holds under all circumstances. As such, evidentialism “leaves the door open” that, as unlikely as it is, the Bible might be false. Some evidentialists would claim that while their arguments from evidence do not establish the certainty of Christianity, the internal testimony of the Holy Spirit closes the gap. In other words, the evidence indicates that the Bible is probably true, getting very close to certainty, and the Holy Spirit confirms conclusively in our heart that the Bible is definitely true.

The classical approach is primarily deductive (though it may use some induction as well), and generally operates in a two-step approach. In the first step, the classical apologist establishes that God exists. This is usually done with one of three arguments: the cosmological argument, the teleological argument, or the ontological argument. Only then will he proceed to argue for the other truth claims of Christianity on the basis of other facts such as fulfilled predictive prophecy. The classical apologist appeals to man’s rationality as the ultimate standard for truth.

Presuppositional Apologetics

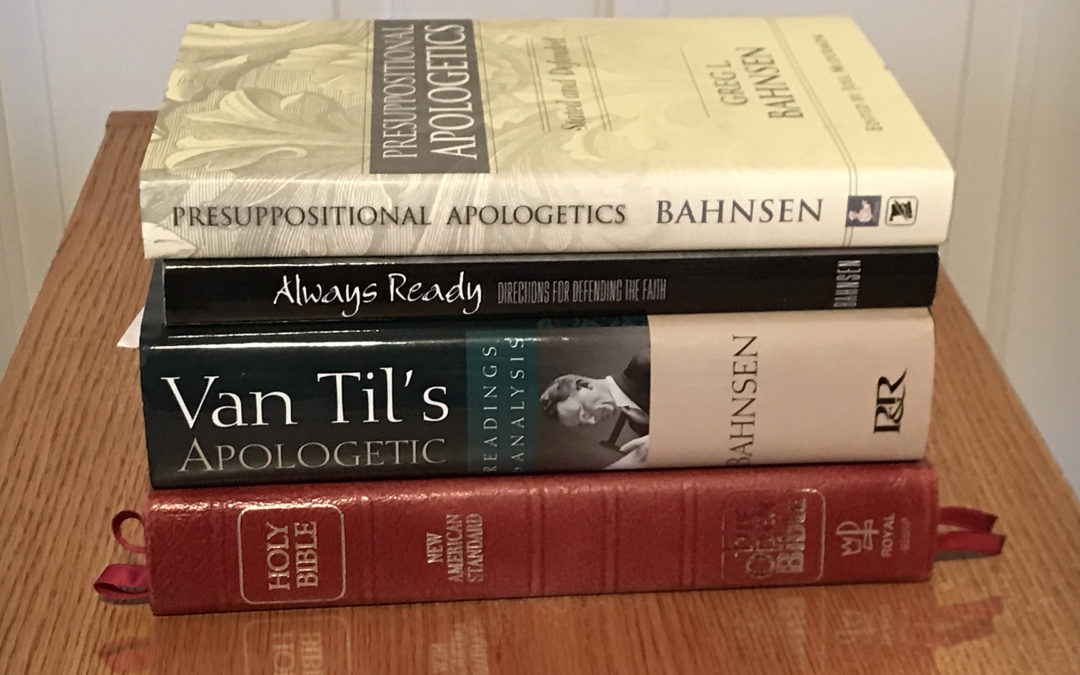

I am a presuppositional apologist. By this I refer to the apologetic method advanced by the 20th century apologists Greg Bahnsen and Cornelius Van Til.[2] The presuppositional method differs from classical and evidential apologetics in that it does not accept secular reasoning as sufficient to judge the truthfulness of Scripture. Whereas evidential apologetics appeals to man’s understanding of the evidence/facts as the ultimate standard for truth, and whereas classical apologetics accepts man’s understanding of logic and rationality as the ultimate standard for truth, presuppositional apologetics accepts God as the ultimate standard for truth (see Proverbs 1:7, Colossians 2:2-3, John 14:6). Hence, God’s Word – the Bible – is our ultimate, objective, propositional, and unquestionable standard for all truth claims, even when defending the Bible.

Accepting the Bible as our ultimate standard for truth does not mean that all truth is contained in the Bible. There are things that are true (E=mc2, Jupiter is larger than Mars, Antarctica is generally colder than Houston) that are not written in the Bible. Rather, the presuppositional apologist accepts the Bible as giving us the proper worldview foundation on which all other truth claims are built (Matthew 7:24-27). As the ultimate standard for truth, everything the Bible affirms must be true, and nothing that contradicts the Bible can be true.

The presuppositional method is based on the biblical teachings that (1) God is the source of all knowledge[3] and His Word (the Bible) is the ultimate, infallible standard for truth[4], (2) man has been made in the image of God with the capacity to think in a way that is consistent with God’s character (rationally)[5] and (3) with sensory organs that have been designed by God such that they are basically reliable,[6] but (4) the mind of man has been corrupted by sin such that man will not (without help from God) consistently reason correctly (logically) about spiritual issues[7]; (5) God has made Himself inescapably known to all people; knowledge of God and His moral standard has been hardwired into the core of our being,[8] but (6) men in their sin are not grateful to God but instead suppress their innate knowledge of God and become foolish; they are self-deceived.[9]

Most apologetic methods tacitly accept the unbeliever’s self-deception. In other words, they treat a professed atheist as if he really is unaware of God and that if only he were exposed to the right evidence he would be convinced on his own terms that God exists. In contrast, the presuppositionalist rejects the unbeliever’s worldview as irrational, rejects his profession of atheism (or any other false religion) as self-deception, and attempts to expose the unbeliever’s suppressed knowledge of God. Usually, this is done by showing how any alternative to Christianity would make human experience and reasoning completely unintelligible. We’ll leave the details to future articles. The point here is that the presuppositionalist never accepts the secular worldview as sufficient to judge God’s Word, and never abandons the Bible as his or her ultimate standard for all truth claims.

Of course, many evidentialists and classical apologists would accept that the Bible is actually the ultimate standard for truth – except when defending it. “After all,” many would say, “we cannot appeal to the Bible when we are trying to establish to others that the Bible is true; that’s circular reasoning. We must appeal to some other standard.” Hence, the evidentialist and classical apologist generally take one of three positions:

(1) The Bible (though it happens to be true) is not the ultimate standard for truth.

(2) The Bible is the ultimate standard for truth for all matters except its own defense.

(3) The Bible is the ultimate standard for all truth, but we must pretend that it is not when defending it to unbelievers.

The problem with positions 1 and 2 is that they are not true. God is the source of all knowledge (Proverbs 1:7), and hence His Word is the infallible foundation for all truth claims. The problem with position 3 is that it is immoral. If we implicitly or explicitly tell the unbeliever that his non-Christian philosophy is sufficient to judge the truthfulness of the Bible, then we are lying to him. Non-Christian philosophy is wrong.

The distinguishing feature of presuppositional apologetics is that we hold that the Bible is the ultimate standard for all truth claims, including its own defense, and we refuse to pretend otherwise when dealing with unbelievers. Hence, a better name for the presuppositional method would be “biblical authority apologetics.” We do not accept that secular reasoning (reasoning from non-biblical presuppositions) – if applied consistently – will necessarily reach the conclusion that the Bible is true. It might do so by accident. But since we reject non-biblical presuppositions as false, any conclusion derived from them is unreliable.

Other apologetic methods accept (at least for the sake of argument) the unbeliever’s standards of reasoning (science, logic, etc.) apart from the biblical worldview and then attempt to show that the Bible is likely true when such secular reasoning is consistently followed. In contrast, the presuppositionalist rejects the unbeliever’s reasoning as wrong and sinful. He or she exposes the absurdity of the unbeliever’s worldview, and invites the unbeliever to stand on the Christian worldview.

One way to think of this distinction is to ask, “who is the ultimate judge of what is true, God or man?” The classical and evidential approaches essentially say to the unbeliever, “Your mind is more than sufficient to correctly judge the evidence and reason properly. Please let me act as God’s defense attorney and present evidence and arguments. You can be the judge, and you will see that the Bible is true and God is worthy of your worship.” Conversely, the presuppositional approach essentially says to the unbeliever, “Your way of thinking is wrong because you have sinfully rejected God’s Word, you have suppressed your knowledge of God, and you need to repent because God will judge you. You are the one on trial, not God.”

You can see why the classical and evidential methods appeal to man. It’s far more enjoyable to be the judge than to be on trial! The evidential and classical approaches stroke the unbeliever’s ego by letting him pretend to be the judge of truth. But such an approach is immoral. Why? The unbeliever is not the judge of truth. God is. The unbeliever is not in an intellectual position to judge God’s Word; rather, God’s Word is the standard by which the unbeliever will be judged (Revelation 20:12). It is therefore dishonest to give the unbeliever the impression that he has the right and the intellectual ability to judge God’s truth claims by the unbeliever’s own fallacious and sinful reasoning. The presuppositional method is offensive to the sinful mind precisely because the presuppositionalist tells the (unpleasant) truth.

Again, a Christian’s apologetic method is revealed by how he or she answers the question, “how do we know that the Bible is true?” The evidentialist answers “because of evidence.” He or she may appeal to scientific evidence, or historical evidence. The classical apologist answers “because of rational reasons” and proceeds to argue for the existence of God, and then to argue for specific truth claims of Christianity. The presuppositionalist answers “because of the impossibility of the contrary.” He or she then shows how the Bible is the necessary foundation for human experience to be intelligible, and how any alternative to the biblical worldview would make knowledge impossible (Proverbs 1:7). We will explore the details later.

Misconceptions of Presuppositional Apologetics.

Unfortunately, presuppositionalism is the most misunderstood method of apologetics. Most Christians misunderstand it and this unfortunately often results in straw-man arguments against the method. I have read many, many articles by well-meaning Christians who argue against the presuppositional method. However, I have yet to read a single one that correctly represents the method. Consider, for example, my debate with Richard Howe (who holds to classical apologetics). His arguments against the presuppositional method were essentially all straw-man fallacies, as shown in my response. You can read the entire debate here. Before going into any depth on what presuppositional apologetics is, it is helpful to refute some of the more common misconceptions:

Misconception 1: “Presuppositional apologetics is fideism. It just ‘presupposes’ that Christianity is true and goes from there.” The irony of this misconception is that presuppositional apologetics is as opposite of fideism as is possible! Recall, fideism is accepting something without rational reasons. However, the presuppositional method establishes the rational certainty of Christianity. The Fideist claims that no one can really prove that the biblical God exists. Evidentialists argue that God very probably exists. However, the presuppositionalist argues that everyone already knows for certain that the biblical God exists, and that this can be conclusively demonstrated.

Misconception 2: “Presuppositionalists don’t use scientific and historical evidence.” This erroneous belief may come from the assumptions about terminology: i.e.. “evidentialists must use evidence, whereas presuppositionalists just presuppose.” But nothing could be further from the truth. Presuppositionalists do use scientific and historical evidence. (And evidentialists have their presuppositions.) Some presuppositionalists (like myself) use a great deal of scientific and historical evidence to illustrate the truth of Scripture. The difference is in the way we use the evidence. The evidentialist appeals to the evidence as the foundation by which we know that the Bible is true, whereas the presuppositionalist appeals to the Bible as the foundation by which we know that evidence is true.

Misconception 3: “Presuppositionalists reject all the classical evidences for God, such as the cosmological and teleological arguments.” Again, the claim is ironic because the presuppositional apologist recognizes that all evidence is evidence for God, because apart from God no evidence would be intelligible. And what of cosmological and teleological arguments? The presuppositionalist would object to the way in which classical and evidential apologists use such arguments – as if the unbeliever can correctly interpret them within his own worldview. Nonetheless, such arguments may be worded in such a way as to confirm the Christian worldview. In fact, many evidential and classical arguments can be adjusted so that they do not pretend that the Bible is less authoritative than external evidence or man’s “reason.” Remember, the difference between the presuppositionalist and evidentialist is not the evidence we use, but how we use it.

Misconception 4: “Presuppositionalism is just fallacious circular reasoning, in contrast to other apologetic methods.” There are two errors in this objection, and both are due to lack of education in epistemology (the study of knowledge), and ignorance of the Münchhausen trilemma in particular. The first error is in thinking that all forms of circular reasoning commit the petitio principii fallacy – that they beg the question. They do not. The second error is in thinking that alternatives to presuppositionalism somehow avoid circular reasoning. They do not. We’ll examine this fascinating topic in upcoming articles.

Misconception 5: “Presuppositionalists reject natural revelation.” Natural revelation refers to the fact that God has revealed Himself in nature, and has hardwired us to recognize the natural world as the creation of God. No presuppositionalist would reject this because it is biblical (Romans 1:19-20). The misconception may be due to the fact that the presuppositionalist rejects natural theology, which is something else entirely. Natural theology is knowledge of God based on nature (observed facts and experience) apart from divine revelation. That last phrase “apart from divine revelation” is critical. The problem is that apart from God’s revelation, we would have no idea how to interpret anything in nature. We can indeed learn about God through nature only because He has revealed Himself to us. Apart from divine revelation, we could know nothing.

Misconception 6: “Presuppositionalists reject the idea that believers and unbelievers have intellectual common ground.” Again, the opposite is true. We affirm that believers and unbelievers have common intellectual ground since we are both made in God’s image and hardwired by God to know certain basic truths. This is what makes our conversations intelligible. What we deny is “neutral ground.” The common intellectual ground we share with unbelievers (laws of logic, reliability of sensory experience) is not neutral; it belongs to God and is only intelligible within the Christian worldview.

Misconception 7: “Presuppositionalism is only useful against atheists. It only demonstrates that there is a God.” In reality, presuppositionalism is an argument for the Living God as described in the Bible. It cannot consistently argue for Krishna, Allah, or any other so-called god. It is therefore a demonstration of the truth of the Christian worldview, which is necessarily a refutation of any contradictory worldview. The presuppositional method – properly employed – will refute any worldview that is contrary to Scripture.

Misconception 8: “Presuppositionalism is a matter of degree. Some people are evidential presuppositionalists.” People who say they are “evidential presuppositionalists” are very confused because the term is an oxymoron; it is self-contradictory. Remember, the key distinctive of the presuppositional apologetic is that the Bible is the ultimate standard for all truth claims, including its own defense. But in evidentialism, the Bible is not the ultimate standard at least when it comes to its own defense. Those two positions are contrary to each other. Therefore, they cannot both be true. A person either bases his apologetic on biblical authority (in which case he is presuppositional) or he does not.

Misconception 9: “Presuppositionalists reject rational argumentation because they believe that only God can change the heart of an unbeliever.” While we recognize that only God can change someone’s heart, we fully embrace rational argumentation. After all, God can use our arguments as part of the means by which He grants an unbeliever repentance. God ordains not only the ends, but the means as well.

More to Come

The above is intended as an introduction. Due to the frequent straw-man arguments waged against presuppositional apologetics, it is necessary to refute the most prominent misconceptions before a fair analysis of the method can be conducted. In upcoming articles, we will explore the presuppositional method in some detail, and respond to additional misrepresentations of it.

[1] The word ‘apology’ has come to mean virtually the opposite of what it originally meant. Today, when we apologize, we mean to admit that we were in the wrong and are expressing regret. But originally, to give an apology was to give evidence that we are in the right: that we are not guilty of the charges against us.

[2] Gordon Clark had an apologetic method that is also sometimes called “presuppositional.” His method has some similarities with the presuppositionalism of Bahnsen and Van Til, but significant differences as well. In this article, I will only be referring to and defending the Van Tilian version.

[3] Proverbs 1:7; Colossians 2:2-3; John 14:6

[4] 2 Timothy 3:16; Psalm 119:160; Matthew 4:4, 5:18

[5] Genesis 1:26-27; Isaiah 55:7-8

[6] Proverbs 20:12; Matthew 13:16

[7] 1 Corinthians 2:14; Romans 1:21-22, 25; Isaiah 55:7-8; Philippians 1:29

[8] Romans 1:18-20, 2:14-15; Psalm 19:1,4

[9] Romans 1:18-25; James 1:22