The big bang is a secular story of the origin of the universe. It was designed to explain the origin of stars, planets, galaxies, and even the universe itself without any need for God. The big bang is not compatible with the history recorded in Genesis. But if we didn’t have Genesis, would it be reasonable to believe in a big bang? Does the big bang have scientific merit? To answer these questions, we need to understand exactly what the big bang story is.

A Summary of the Standard Model of Cosmology

The big bang is also called the standard model because it is the working paradigm in which most scientists attempt to understand how the universe came to be the way it is today. Many people have misconceptions about this model, so we begin with a brief summary, and then explain each of the steps in greater detail.

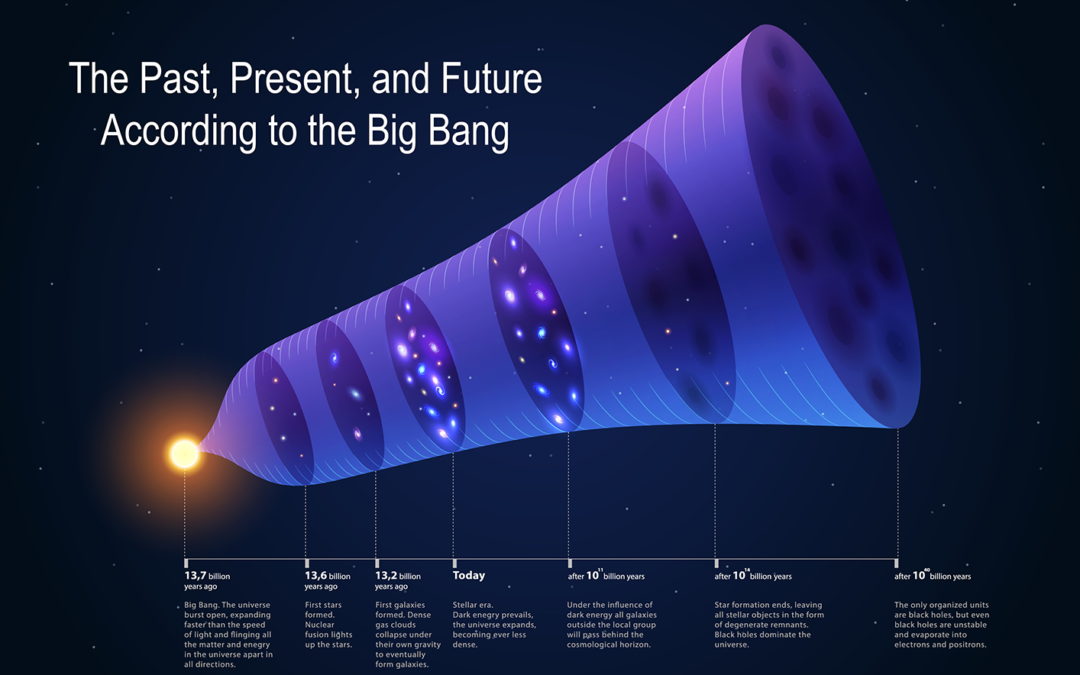

- The entire universe is contained in a point of no size and infinite temperature.

- This point rapidly expands, and the energy cools.

- Some of the energy becomes matter – hydrogen and helium.

- Some of the matter condenses into stars and galaxies.

- Stars produce all the heavier elements which become dust.

- Dust condenses to form planets.

- In the future, the universe expands forever, and dies a “heat death.”

So, the standard model begins 13.8 billion years ago with the entire universe contained in a point of zero size called a singularity. The energy that would later become everything else is contained in this point, and there is literally nothing that is not contained within it. The energy density would be infinite, and therefore the temperature would be infinite.[1]

Physicists and mathematicians are no strangers to singularities. The physics discovered by Einstein shows that black holes have a singularity in their exact center which contains all the mass of the black hole. However, the singularity of a black hole is surrounded by space. You can orbit around a black hole in that surrounding space. Every black hole is surrounded by an event horizon – a conceptual sphere marking the “point of no return.” Anything entering the event horizon of a black hole can never leave, and must eventually intersect the singularity.

But the big bang singularity is an entirely different type of singularity. It is not surrounded by anything – not an event horizon, and not even empty space. This is because all of space is contained within the singularity of the big bang, and none is outside. So, you cannot orbit around the big bang singularity because there is no space outside of it in which to orbit. The big bang singularity is not surrounded by an event horizon (or anything else). It is called a naked singularity because it is not “clothed” with an event horizon the way black holes are. Many people ask the question “where did the big bang supposedly happen?” But since all of space is contained within the singularity, the only answer the standard model can give is “everywhere.”

This singularity then rapidly expands becoming a three-dimensional space, packed with energy. This is the “big bang” although the name can also be used to refer to the standard model in its entirety. It is important to realize that this “explosion” is not like explosions we observe today. We observe explosions of material into the surrounding space. But the big bang is a rapid expansion of space itself. There is no matter at this stage because the temperature is too high to have atoms. As the universe expands, the density drops because the volume is increasing. This causes the temperature to drop.

Within minutes, the temperature drops to a few billion degrees and some of the energy is cool enough to become particles like protons, neutrons, and electrons. Some of the protons and neutrons combine into atomic nuclei, but only for the three lightest elements: hydrogen, helium, and trace amounts of lithium. The temperature is still too hot for ordinary neutral atoms; electrons have far too much energy to remain bound. Around 380,000 years after the initial bang, the temperature becomes cool enough for electrons to bind to nuclei, and neutral atoms are born – but only hydrogen, helium, and lithium. No other elements exist at this point. With neutral atoms, the universe becomes transparent for the first time.

About 400 million years later, some of the hydrogen gas collapses into stars which comprise galaxies. Since the only elements available at this point are hydrogen, helium, and lithium, the first stars would be made of only these elements. These are called population III (“population three”) stars.

Stars fuse hydrogen into helium in their core. Once the hydrogen is all converted, astronomers believe that stars can briefly fuse helium into elements like oxygen and carbon. But these elements remain in the core of the star. However, some stars are exceptionally massive. Though rare, these stars are so massive that when they exhaust the fuel in their core, they can blow apart catastrophically in a process called a supernova. This process is so energetic, that it can fuse heavier elements from the lighter ones. The blast carries some of these heavy elements into space. According to the standard model, all the heavy elements in the universe were produced by stars in this fashion.

The heavy elements are dispersed in space, though some of the atoms can stick together to form dust grains that are suspended in clouds of hydrogen and helium gas. Some of these gas clouds condense under the force of gravity to form new stars. And since these clouds have trace amounts of heavy elements, so do the stars that form from them. These are called population II stars. A small percentage of population II stars are ultra-massive, and so they will exhaust their fuel quickly and explode in a supernova. This will further increase the heavy elements in the cosmos. Stars that form from these secondary supernovae will have even more heavy elements than the stars that preceded them, and are referred to as population I stars.

As a population I or II star is forming from its gas cloud, some of the dust collects together forming larger objects that orbit in the disk surrounding the central mass (the proto-star). Such masses form the gravitational seeds for planets. As gas and dust continue to collect around these seeds, they grow larger until the accreting material is exhausted, forming planets. These planets would all be surrounded by thick atmospheres of hydrogen gas since the hydrogen atoms vastly outnumber all others. Eventually the proto-star has accumulated enough mass to induce hydrogen fusion in the core, becoming a full-fledged star. The energy of stellar winds blows away the hydrogen atmospheres of any planets that orbit close to the star, with only their rocky solid cores remaining. But the stellar winds are less powerful with increasing distance. So the more distant planets remain hydrogen gas giants. This model explains why the inner planets in our solar system (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars) are small and rocky, whereas the outer planets are large gas giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune).

The standard model also predicts the state of the universe in the distant future. As the universe continues to expand forever, energy will continue to go from a useable to a useless form. Energy is useable when there are temperature differences at different locations; the flow of thermal energy (heat) can be used for useful work. But, in the standard model, energy eventually comes to equilibrium and no useful energy will remain. This is called “heat death.” At that point, all stars will have long ceased as their available fuel is exhausted. Black holes form and grow, and low-level electromagnetic radiation pervades all space. Even further in the future, black holes themselves may “leak” Hawking radiation and “evaporate” leaving only radiation in equilibrium. No life will be possible.

Is it Science?

The above scenario explains many of the characteristics of the observed universe. But of course, that is what it was invented to do. The question remains, is the big bang science? As always, it will be necessary to define our terms in order to answer this question rationally. By ‘science’ I refer to the method of testing claims by observation and experimentation, or the body of knowledge acquired by such a method. Testability by repeatable observation and experimentation is the key distinguishing characteristic of science. So, we must ask, of the above seven central claims of the standard model, which of them have been observationally or experimentally demonstrated? Let’s consider them one at a time.

Has step 1 been scientifically demonstrated? Have we observed a singularity? Have we observed a universe in which all energy and even space itself is contained in a point of no size? Have we observed anything with infinite energy density and infinite temperature? None of these things have been observed. None have been experimentally demonstrated. No one has created a singularity in a laboratory. No singularities have been directly observed. And the only singularities for which we have indirect observational evidence – namely those in the core of a black hole – are of an entirely different variety. They are surrounded by an event horizon. There is no scientific evidence whatsoever of a naked singularity.

In fact, there is a principle in physics which would seem to forbid the existence of a naked singularity. Called the “cosmic censorship hypothesis”, the principle states that all singularities must be surrounded by an event horizon. Usually, the big bang is arbitrarily exempted from this principle (because it would violate it.) The hypothesis is not proved, but there are no observational counterexamples. In any case, there is no observational or experimental evidence for a big bang singularity, nor for any of the conditions associated with it. It is therefore not scientific. That doesn’t automatically make the idea false of course. It just means that it lies outside of the scope of science.

In step two, the three-dimensional universe expands from this singularity. There is some observational evidence that the universe is expanding. We cannot observe the expansion directly, but redshifts that increase with distance would be a natural result of expansion, and these redshifts are observed. So there is some scientific support for expansion. Furthermore, when energy density drops, the energy cools. We do know that this happens from laboratory experiments.

However, the big bang is claiming that the expansion began from a point of zero size. This is essential to the big bang model, and yet this has not been observed. It follows that if we have never observed a singularity then clearly, we have not observed a singularity expand into a universe. Nor has any laboratory experiment demonstrated a universe expanding from a singularity. So this step does not qualify as science either, although there are aspects of it (expansion and cooling) that are consistent with what we do observe scientifically.

Step 3 is one that, at first, seems to fit the definition of science. Physicists can smash particles together at extremely high speed. And particles of matter can form from the energy of the collision. In particle accelerators, we can make electrons, protons, and neutrons from energy. This is testable, repeatable, laboratory science.

However, the big bang’s claim is not merely that matter can be created from energy. Rather, it claims that all the matter in the universe did in fact form from energy. This is a substantially different claim. It is one thing to say that car engines can produce carbon monoxide – this can be scientifically demonstrated. It is quite another to claim that all carbon monoxide in the universe came from cars. The claim that all matter in the universe came from energy is something that has not been observed and cannot be observed. Therefore, it is not a scientific claim.

In fact, there are significant scientific problems with the notion that all matter in the universe came from energy in the big bang. Laboratory experimentation has shown that we can make matter from energy. But in all cases, the reaction also produces an equal amount of antimatter. Antimatter has the same properties of ordinary matter, except the electrical charges of the particles are reversed. So an anti-electron (often called a positron) is just like an electron, except an electron has a ngative charge and a positron has a positive charge. Whenever we produce an electron, we also get a positron. Science has demonstrated that whenever energy becomes matter, it also produces an exactly equal amount of antimatter. There are no exceptions.

This is significant because the universe is essentially matter-only.[2] If the matter in the universe came from energy, then the process should have produced an equal amount of anti-matter. In other words, if step 3 of the standard model had actually happened, then the universe should be 50% matter, and 50% antimatter. But observations show that the universe is virtually 100% matter. Hence, not only is step three not scientific (not observable, not repeatable), it appears to be contrary to scientific observations.

In step 4 of the standard model, some of the hydrogen and helium gas condenses into stars. This could theoretically happen if the gas cloud has sufficient mass and has cooled to the point that its internal outward pressure is less than the inward force of gravity.[3] For all the claims of “star-forming regions,” a person might think that this has been observed. But it has not. No one has seen a star form. No one has seen gas in the process of collapsing into a star. We do observe clouds of hydrogen gas, and we do observe stars. But we do not observe gas clouds that are contracting into stars. Considering there are over 100 billion stars in our galaxy alone, it is truly remarkable that we see not even one in the process of formation. Again, this doesn’t automatically make the claim of star formation false. But it is not scientific because it is not observable in the present.

In step 5, we at first seem to have a claim that might be classified as science. The sun apparently is fusing hydrogen into helium in the core. This process produces neutrinos, which stream away from the core of the sun. And we have instruments that can observe these neutrinos as they arrive at Earth. These testable, repeatable observations are good science, and seem to confirm the fusion of hydrogen into helium in the solar core.

But what of the claim that heavier elements are produced in supernovae explosions? This is much harder to test, although the idea does have theoretical support. The energy of a supernova is sufficient, in theory, to produce some of the heavier elements. When a supernova occurred in 1987, neutrino detectors were able to observe some of the neutrinos coming from this event. So, we at least have some indirect observational support for the idea.

But again, the claim in step 5 is not merely that heavy elements can be produced in a supernova. Rather, the claim is that all the heavy elements in the universe were produced this way. This obviously has not been observed, because we cannot scientifically observe the origin of most elements. While plausible, step 5 does not qualify as science. The origin of most heavy elements has not been observed and cannot be repeated in a laboratory.

In step 6, the heavy elements have collected into dust grains, which continued to grow until they form planets. Is this science? Have astronomers observed planets growing as they accumulate dust grains? We now know of several thousand planets which orbit various stars in our galaxy. But we have not observed any planets in the process of formation. There is some evidence of disks of material orbiting stars. And some secular astronomers have supposed that planets are forming in such disks. But this has not been observed. It is merely a conjecture.

What about the observation of the planets in our solar system? The idea of planets forming from dust, and then the solar wind blowing away the leftover hydrogen from the inner planets but not the outer ones, would account for the planets in our solar system. The problem is that most other solar systems so far explored are not this way. Many stellar systems have gas giant planets larger than Jupiter orbiting closer to their star than Mercury’s distance from the sun. So not only do we not have observations of planets forming, but the observations we do have are inconsistent with the expectations of that model.

Clearly, step 7 cannot be observed or experimented upon because it lies in the future. We cannot observe what the universe will do, only what it is doing. Regardless of how reasonable this conjecture may be, it is not science by definition.

Conclusions

Really, none of the steps of the standard model fall under the definition of science. None of them have been scientifically demonstrated. They are not testable or repeatable in the present. Only a portion of step 2 has any actual observational support; namely, observations of redshifts are consistent with universal expansion. But the notion that such an expansion began as a singularity has not been observed, nor has it been demonstrated to be possible by experimentation. As such, it does not qualify as science. The big bang model is not science.

However, that doesn’t make it false. Many things are true that do not fall under the category of science. Historical truths cannot be tested by observation and experimentation because the past is gone and is not observable. But it is still reasonable to believe in well-documented historical truths. Certain logical truths cannot be demonstrated by the methods of science, yet it is reasonable to believe in them. So, despite the fact that the big bang model is not science, we might ask, “Is it reasonable to believe in it anyway?”

Not all truth claims can be tested by the scientific method. This is obviously the case with truth claims about the distant past or the distant future. We cannot observe or experiment on the past because it is gone. We cannot observe or experiment on the distant future because it has yet to occur. And yet, we have beliefs about the past, and beliefs about the future. The big bang is a conjecture about both the past and the future. And although it is not science, someone might argue that there are good reasons to believe in the big bang anyway. We will explore this issue in the next article. Until then, we have already seen that the big bang is contrary to the history recorded in the Bible. Christians therefore should reject the big bang as false, and should now be equipped to refute the claim that the big bang is somehow scientific. It isn’t.

[1] This simplified explanation leaves out quantum effects which may prevent the singularity from having a size that is mathematically zero, though it would be smaller than a proton. However, relativity allows a size of zero.

[2] There are only infinitesimal trace amounts of anti-matter in the universe, but these are produced by high-energy local sources and are almost immediately destroyed when the anti-particles come into contact with ordinary matter.

[3] This condition is called the Jean’s mass.