In this article, we will examine a particularly embarrassing mistake made by Phillip Dennis in his fallacious attempt to prove the one-way speed of light in all directions must be the same as the round-trip speed. As with all his previous attempts, we will find that Dennis committed the fallacy of begging the question. Namely, he tacitly assumed an equation that arbitrarily presupposes the one-way speed of light at the start. This was the same error made in his previous attempts that I refuted last year (Lisle 2024). What makes his latest mistake particularly embarrassing is that it has already been refuted over 100 years ago (Eddington 1923)! Moreover, it has been refuted multiple times in the last century – including in my book, The Physics of Einstein (Lisle 2018).

By way of a brief review, Phillip Dennis has attacked the ASC model – a model showing that distant starlight does not require millions or billions of years to reach earth. The model is possible due to a principle in relativistic physics known as the conventionality thesis. As Einstein pointed out, the speed of light on any purely one-way journey cannot be objectively measured (without tacitly assuming it) because the one-way speed of light is a humanly stipulated convention.[1] We can even set the one-way speed of light to be infinity when directed toward the observer – a convention that all ancient cultures implicitly used (Jammer 2006). Dennis believes that Einstein is wrong and that the one-way speed of light must be c in all directions – the same as the round-trip speed. However, Dennis has been unable to prove this because all of his arguments so far have been viciously circular. That is, they arbitrarily assume that the one-way speed of light is isotropic (the same in all directions) at the start. This assumption/stipulation is called ESC. However, arbitrarily assuming ESC does not disprove ASC.

Recently Dennis has claimed that two experiments prove the one-way speed of light must be c in all directions. We analyzed the first of these in the previous article and found that Dennis erred in his reasoning by assuming ESC at the first step. The observations are perfectly consistent with ASC, in which the one-way speed of light can be infinite in one direction.

In this article we will examine the second experiment, which is based on a method called slow clock transport. Physicists over the last century have proved that slow clock transport cannot objectively measure the one-way speed of light as we will examine below. However, Dennis is apparently unfamiliar with such literature.

What is particularly indicting is that this type of experiment was already refuted in my book, the very book that Dennis is supposedly criticizing. He just doesn’t seem to read carefully. Indeed, The Physics of Einstein (Lisle 2018) discusses slow clock transport in pages 214-215 and shows mathematically that this method cannot be used to determine the one-way speed of light without first assuming it (pages 227-230).[2] Furthermore, a specific case of this method is explored in pages 259-263 and mathematically demonstrated to give the same observational results whether using ASC or ESC. This proves that such an experiment cannot be used to falsify one synchrony convention over the other, contrary to Dennis’s assertion.

Background: The Importance of Synchronized Clocks

In order to measure the speed of something on a one-way journey from A to B, we need two clocks (or their equivalent), one at location A and another at B. The clock at A is necessary to record the time the object started its journey, and the clock at B is needed to record the arrival time. By subtracting the start time from the arrival time, we get the time of the journey. By dividing the distance (between A and B) by the time of the journey, we get the one-way speed. The difficulty here is that this will only give the correct answer if the two clocks are synchronized – if they read the same time at the same time. If the clock at B reads 2:45 at the same moment when the clock at A reads 12:00, then obviously we will not compute the correct speed for the object making the journey.

In our experiences on Earth, the two clocks only need to be approximately synchronized. When measuring the speed of an Olympic athlete in a race, it makes little difference if the clock at B is 0.0006 seconds behind or ahead of the clock at A. This is close enough for such purposes and will not significantly affect our computation of the runner’s speed. But when measuring something as fast as light, even the smallest difference between A and B will result in very different calculations of light’s speed. Thus, the clocks at A and B need to be exactly synchronized. And this turns out to be impossible without first assuming/stipulating the one-way speed of light – the very thing we are attempting to measure! Here is why:

There are two conceptual ways to synchronize clocks separated by some distance, and both depend on the one-way speed of light. The first method is by signal transmission. Perhaps a radio transmitter could be placed exactly between two clocks located at A and B, respectively. It transmits a radio pulse in both directions, and A and B both set themselves to noon when they receive the radio pulse. But does this mean that A and B are truly synchronized? It would be the case if only we knew that the radio pulse traveled the same speed to A as it does to B (in the opposite direction). But radio travels at the speed of light. So if light travels at a different speed from left to right than from right to left, then so does radio. In other words, this method would only result in synchronized clocks if we already knew that the one-way speed of light is the same in all directions – they very thing we want to measure!

Some people have proposed other types of signals. Perhaps we use an electrical signal to synchronize the clocks. But the problem is that electricity travels at the speed of light! The speed of light is so fundamental to space and time, that any signal we can think of tacitly depends on the speed of light in one-direction, the very thing we do not know. For example, the speed of sound could be used as a signal. But sound is caused by the collision of molecules in a substance. Molecules collide due to electromagnetic fields. And electromagnetic fields travel at – you guessed it – the one-way speed of light. In other words, if the one-way speed of light is not isotropic, then the speed of sound will also be (very slightly) non-isotropic. Thus, to exactly synchronize two clocks using sound signals, we would have to already know in advance the one-way speed of light.

So, synchronizing two clocks by signal transmission cannot be used to objectively measure the one-way speed of light because the speed of the signal depends upon the one-way speed of light. The only alternative left to us is therefore to synchronize both clocks at the same location, and then move them to A and B. This method is called slow clock transport. But does it really work?

It is easy to exactly synchronize two clocks that are at the same location because we can see that they read the same time. However long it took the light to reach our eyes from one clock, it took the same time for the other clock because it is at the same location. Thus, we can be assured that the two clocks are indeed exactly synchronized. We then move one of them to location A and the other to location B some distance away. Now we have two clocks separated by a distance, so we can presumably use them to measure the one-way speed of light. Or can we? Have we made an unwarranted assumption?

Although the two clocks were synchronized when they were together, how do we know that they remained synchronized when they were moved? After all, Einstein discovered that motion affects the passage of time. This is called time-dilation and has been experimentally verified. The very act of moving a clock causes it to tick at a slightly different rate than if it were to remain stationary. And the clocks had to be moved to get one to A and the other to B. During their journey, there is no guarantee that they remained synchronized, and thus there is no way of knowing that they are synchronized now. Is there a way around this problem?

Slow Clock Transport

One interesting aspect of time-dilation is that the effect is stronger at faster speeds. Suppose we had two clocks exactly synchronized at location A. If we moved one clock rapidly to point B and then back to point A, we would find that it is now behind the clock that remained at A. Apparently it ticked slower on its journey than the stationary clock. If we again synchronized the clocks and repeated the experiment, but this time moved the clock slowly to B and back to A, we would find it is still behind the stationary clock but by a lesser amount. As we continue to repeat the experiment at slower and slower speeds, the clock that moved will be closer to being synchronized with the stationary clock at the end of the experiment. The physics of Einstein tells us that in the limit as the velocity approaches zero, the two clocks will be exactly synchronized upon their reunion at A. Apparently the key to keeping the clocks synchronized is to move them as slowly as possible – hence, “slow clock transport.”

Many people have proposed this as a way to objectively synchronize two clocks separated by a distance. That is, synchronize both clocks at the same location and then move one of them as slowly as possible to a distant location. The belief is that the clocks are still synchronized even though separated by a distance. After all, we know if the clock that moved is brought back to A (as slowly as possible) it will still be synchronized with the stationary clock.

But a critical unwarranted assumption has been made. Yes, a clock synchronized at A, and moved to B and back to A as slowly as possible will still be synchronized with the other clock upon its return. But how do we know that it remained synchronized with the other clock throughout the journey? In other words, how do we know that the moving clock didn’t lose one second on the outbound journey and then gain one second on the inward journey? We will see below the full time dilation equation shows that this is exactly what happens when the one-way speed of light is not isotropic!

Dennis is apparently ignorant of this effect although it has been abundantly discussed in the technical literature. Indeed, John Winnie derived the full, synchrony-independent time-dilation equation over fifty years ago (Winnie 1970a&b). (In Winnie’s second paper, he refuted the very mistake that Dennis committed in his.) Furthermore, I included this equation in my book, The Physics of Einstein: page 222, equation 17.1 (Lisle 2018). I then used this equation to prove mathematically that slow-clock transport cannot be used to measure the one-way speed of light (pages 227-230).

Thus, Dennis’s argument was already refuted in this book before he even made it! In fact, it has been refuted multiple times in the technical literature over the past century as will be shown below.

Nonetheless, let’s examine Dennis’s argument and see why it fails.

The Experiment

Dennis analyzes the New Horizons spacecraft 9.5 years into its journey to the outer solar system, at which point it was 4.76×109 km distant. He then attempts to compute the proper time (essentially the spacetime interval) between that event and the start of the mission. He claims: ![]()

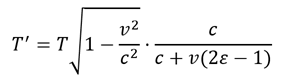

But that’s the wrong formula for this question. That’s the proper time in ESC coordinates![3] In other words, that formula presupposes that the one-way speed of light is exactly c in all directions – the very thing Dennis thinks he is proving. So again, Dennis has fallaciously begged the question at the first step by assuming ESC coordinates that set the one-way speed of light to be c, and then he concluded that that one-way speed of light must be c. In fact, this is exactly the same error Dennis made in his first paper, which I have already refuted (Lisle 2024). Namely, he had assumed ESC coordinates for the spacetime interval and then showed that this leads to the one-way speed of light being c – the very thing it assumes. It is not logical to think you have proved something by arbitrarily assuming it at the first step. As I already pointed out in my previous refutation of Dennis, the correct formula in ASC coordinates is:

The above is equation 3 of my original paper refuting Dennis (Lisle 2024), but converted to proper time and setting Δy = Δz = 0. Using the ESC version of the formula, Dennis computes the total time dilation of New Horizons (Δt – Δt’) at 0.41 seconds – assuming ESC coordinates. But when we use the ASC version of the formula, we compute the total time dilation (Δt – Δt’) of: 15,900 seconds; or 4 hours, 25 minutes. Remember, time dilation is generally larger in ASC coordinates than in ESC coordinates (Lisle 2018, p. 223).

Dennis states, “Sample data available on the NASA website states that the distance of New Horizons spacecraft at the encounter with Pluto was D = ~4.7 × 109 km, and the computed time of flight (difference of earth clock at reception at the DSN and New Horizons’ downlinked clock reading) during the encounter was ~4 hours 25 minutes.”

But that is exactly what we would expect if ASC is correct, and the inbound one-way speed of light/radio is instantaneous! Namely, the accumulated time dilation for the spacecraft is 4 hours and 25 minutes behind Earth clocks. And since that is exactly what was detected, it follows logically that the radio transmissions reached Earth immediately.

Dennis fallaciously assumes that the 4-hour, 25-minute difference is due to light travel time and falsely concludes that the one-way speed of light must be about 2.956 × 105 km/s. But this is because he assumed ESC in his time dilation computation, thereby begging the question. Had he used ASC to compute the time dilation, he would have found that the clock on New Horizons is behind Earth clocks by 4 hours and 25 minutes. Thus, the light travel time is zero!

Dennis didn’t bother to do the calculation using ASC coordinates or he would have realized that it makes exactly the same prediction for the radio transmissions received from New Horizons as ESC coordinates do. Instead, he assumed ESC coordinates in his first equation and solved for consistency. He arbitrarily assumed that such results are inconsistent with ASC, but he didn’t bother to do the computation. This is again the confirmation bias – the same mistake in reasoning Dennis made in his first paper on this topic.

There really is no excuse for Dennis’s mistake here because I gave him the correct synchrony-independent spacetime interval formula in my refutation of his previous paper (equation 2). Furthermore, I also gave the synchrony-independent time dilation formula in my book on page 222 (equation 17.1) and also referenced John Winnie’s 1970s papers that derive this formula (Winnie 1970a&b). The synchrony-independent time dilation equation is:

When using ESC coordinates, we set ε = ½, and the second term reduces to unity, leaving the equation dependent only upon the square of velocity (that’s what Dennis assumed). Thus, under ESC, time dilation will be very small for small speeds (v << c). This was the fallacious question-begging assumption made by Dennis. However, using ASC coordinates, we set ε = 1, and the second term dominates for low speeds because it has a linear term. Thus, time dilation cannot be neglected even at relatively slow speeds. Notice also that the linear term is sign dependent, meaning that time dilation will be different depending on the direction of travel.[4]

So Dennis falsely concludes, “This empirical observation is a direct refutation of the Reichenbach prescription and Lisle’s thesis” (emphasis in the original). But we have proved just the opposite! Namely, these results are completely consistent with ASC when we do the math that Dennis didn’t bother to do. And I again have to point out that the conventionality thesis is not “Lisle’s thesis” – it is Einstein’s (Einstein 1916).

He then states, “If we had a large telescope and a clock on the exterior of New Horizons, the image would show a clock reading 4.5 hours in the past.” Yes, it would! This is because, according to ASC, time dilation over 9.5+ years has added up to about that amount. Therefore, the light must reach Earth instantly in order for us to see that time. Otherwise, we would see a time of over 9 hours in the past.

Dennis fallaciously asserts, “We do see an image of the past as it was, and which is no longer” (emphasis in original). This again begs the question. It would be the case if and only if one assumes ESC. Under ASC, we are seeing these images in real time, but the New Horizons clock has been ticking slightly slow over the years due to time dilation and is now over 4.5 hours behind clocks on Earth. We proved this mathematically.

And that’s the point! This is why slow clock transport cannot be used to measure the one-way speed of light. We cannot know if a distant clock merely appears to be behind our clock due to light-travel time or is actually behind our clock due to time dilation. Both ESC and ASC predict exactly the same observational outcome! This must always be the case because they are merely different spacetime coordinates describing the same underlying reality. I proved this mathematically in pages 227-230 of The Physics of Einstein (Lisle 2018). I would highly recommend that Dennis actually read this book before he attempts to continue to criticize it.

Dennis falsely states, “To maintain ASC in the light of the evidence of these two empirical cases places one into the denialist camp.” But we have seen that in both cases Dennis begged the question. He arbitrarily assumed ESC as the first step in his argument for ESC. In fact, every argument Dennis has made to “prove” ESC both in his previous paper and this one has assumed ESC at the outset!

Perhaps I need to explain to Dennis that this form of argumentation is not logical. It is an error in reasoning called the petitio principii or begging the question. Here is an example of the kind of reasoning Dennis has been using. “I can prove that all elephants in the world are purple. Here’s my proof: (1) All elephants are purple. (2) All elephants in the world are elephants. (3) Therefore, all elephants in the world are purple.” However, the conclusion is merely a restatement of premise (1), which has not been established. So it doesn’t prove anything new; it just assumes it. Likewise, Dennis has arbitrarily assumed equations that assume/stipulate the one-way speed of light is isotropic in order to “prove” that the one-way speed of light is isotropic. This is illogical. He has done this multiple times in his first paper but has continued to make this mistake in his second paper even after I refuted it in the first paper! This is not scholarly.

What Dennis hasn’t done, what he cannot do, is show that ESC must be uniquely true without first assuming an equation or concept that assumes ESC. I demonstrated why this must be the case in my first paper refuting his arguments, but since he cannot refute my argument, he simply ignored it and came up with other arguments that commit exactly the same error. Again, this is not scholarly.

Dennis’s Many Other Mistakes

Dennis states, “A second example of one-way speed of light measurements is available in NASA deep space probes, such as the MESSENGER mission to the planet Mercury and the New Horizons mission to Pluto and beyond. These missions provide a remarkable example of real-world slow clock transport of onboard spacecraft clocks.” These missions are great examples of slow clock transport. But slow clock transport is conventional because it presupposes ESC, as Eddington pointed out over a century ago (Eddington 1923). It cannot be used to measure the one-way speed of light without first tacitly assuming/stipulating it. Again, I have shown this mathematically in pages 227-230 of the book The Physics of Einstein (Lisle 2018). I would encourage Dennis to actually read this book and the many technical papers in the literature that have demonstrated this principle.

Dennis then states, “Undeniably, there has been controversy regarding the slow clock transport method of synchronizing clocks. I am not going to enter that controversy at this point because it is not essential.” Actually, the “controversy” is that slow clock transport cannot be used to measure the one-way speed of light because it must assume the one-way speed of light in order to compute the accumulated time dilation, as Winnie demonstrated in 1970 (Winnie 1970b). Dennis is simply trying to sweep the problems with this method under the rug because they would refute his claim.

Dennis states, “But what I will bring to evidence is that slowly transported clocks, even if no longer synchronized due to time dilation, disprove the infinite speed claim of Lisle.” Of course, we refuted this above. When computing the time dilation in ASC coordinates (which Dennis didn’t bother to do), we found that the speed of the radio transmissions must indeed be infinite. Dennis missed this because he (once again!) had unwittingly assumed ESC in his attempt to prove ESC (the fallacy of begging the question). Namely, he assumed the ESC form of proper time to compute time dilation and falsely concluded that the New Horizon’s clock only appears to be behind Earth clocks due to light travel time. But he failed to do the mathematical analysis in ASC coordinates or he would have noticed that it gives the same observational results while requiring inbound light to have infinite speed. Thus, he again committed the scientific error of confirmation bias.

Dennis states, “If the time dilation is miniscule compared to the one-way light time, a very accurate speed of light can be measured.” This begs the question because time dilation is not miniscule in ASC coordinates. Dennis has simply assumed that time dilation is miniscule because it would be under ESC. But he didn’t do the computation in ASC. We found that under ASC, the accumulated time dilation on New Horizons’s ~9.5-year journey is 4 hours 25 minutes, which is exactly what we saw for the clocks on New Horizons confirming that the incoming radio transmissions are indeed instantaneous.

Dennis states, “In short, ignoring the small amount of time dilation can be considered an experimental error.” As we demonstrated above, this is false. Only if one assumes ESC would the time dilation be negligible. But Dennis didn’t bother to do the computation using ASC coordinates that would have refuted his assertion. Recall we found that the time dilation accumulated to 4 hours and 25 minutes. Both in my book The Physics of Einstein (Lisle 2018), and in my previous paper refuting Dennis (Lisle 2024) I referenced John Winnie’s derivation of the synchrony-independent time dilation formula (Winnie 1970a&b). Apparently, Dennis still hasn’t bothered to actually read the paper and remains ignorant of synchrony-independent relativistic physics. Yet he is attempting to refute it. This is not appropriate.

Dennis states, “One may wonder about time dilation. First, it is important to remember that time dilation is an objective property that depends on the invariant spacetime interval along the spacecraft trajectory.” This is demonstrably false. Einstein showed that time dilation is reference frame dependent, and therefore not “an objective property.” It is not invariant. For example, relative to the New Horizon spacecraft, it experiences no time dilation at all, but clocks on earth experience time dilation; they tick slow relative to New Horizons. The earth experiences the exact opposite; it computes that the New Horizons clock is ticking slow. Time dilation is reference-frame dependent and synchrony-convention dependent. Notice that I proved this mathematically above, contrary to Dennis’s bald assertion.

The History of Slow Clock Transport in the Technical Literature

I always recommend to anyone interested in the conventionality thesis to read at least ten technical papers on this topic before they attempt to write anything on this issue. This is so they will not make the kinds of obvious mistakes that Dennis has made in his two articles. It is the mark of a good scholar to be familiar with the claims and arguments of one’s opponents. Therefore, anyone interested in issues pertaining to synchrony conventions and the one-way speed of light must read at least some of the rich history of technical papers devoted to this issue. It is obvious that Dennis has not read any of these because it has been well established in the technical literature that the slow clock transport method of synchronizing clocks is conventional and mathematically equivalent to choosing the ESC convention. That is, it assumes/stipulates at the outset that the one-way speed of light is isotropic and, therefore, cannot be used to objectively prove this stipulation. So let’s look at such a few of these papers that have been published over the past century.

In 1923, Arthur Eddington demonstrated that synchronizing clocks by slow clock transport was mathematically equivalent to stipulating that the one-way speed of light is isotropic. Thus, it is conventional and not an objective property of nature (contrary to Dennis’s assertion). Eddington states:

Thus the same difference in the reckoning of simultaneity by S and S’ appears whether we use the method of transport of clocks or of light-signals. In either case a convention is introduced as to the reckoning of time-differences at different places; this convention takes in the two methods the alternative forms–

(1) A clock moved with infinitesimal velocity from one place to another continues to read the correct time at its new station, or

(2) The forward velocity of light along any line is equal to the backward velocity (Eddington 1923, emphasis added)

In other words, to assert that slow clock transport establishes synchronized clocks is mathematically the same as asserting the one-way speed of light is isotropic. Therefore, neither method can be used to prove the other without begging the question. Both assertions are equally conventional. Eddington continues, “Neither statement is by itself a statement of observable fact, nor does it refer to any intrinsic property of clocks or of light; it is simply an announcement of the rule by which we propose to extend fictitious time partitions through the world. . . We have here given a theoretical proof of the agreement. . .” (Eddington 1923, emphasis added).

That is, we choose/stipulate the one-way speed of light in some direction, and this establishes how we define simultaneity for some group of observers. That’s the conventionality thesis in a nutshell. Eddington rightly concludes of the signal method and slow clock transport, “We can scarcely consider that either of these methods of comparing time at different places is an essential part of our primitive notion of time in the same way that measurement at one place by a cyclic mechanism is; therefore they are best regarded as conventional” (Eddington, 1923, emphasis added).

An additional early objection to slow clock transport involved the circularity involved in measuring the velocity of the moving clock. After all, a velocity is defined by the displacement of an object divided by the time of the journey – but the time of the journey implicitly requires a synchrony convention. An early solution, proposed by André Metz, was to use the distance divided by the time measured by the moving clock as the velocity, which Metz referred to as “rapidity.” Metz demonstrated that this method yields the same result as stipulating that the one-way speed of light is c in all directions (ε = ½).

Metz’s notion of rapidity was not widely accepted at the time but was revived by Eugene Ives in 1948. He renamed the idea of rapidity as “self-measured velocity.” Ives rejected Einstein’s Theory of Relativity and also slow clock transport as a legitimate means of establishing any sort of simultaneity. But he embraced the concept of “self-measured velocity.”

In 1962, Bridgman proposed using “self-measured velocity” in the limit as it approaches zero as a method of slow clock transport. This form of slow clock transport still implicitly assumes ESC, that ε = ½ (as Bridgman acknowledged). That is, it is mathematically equivalent to simply stipulating that the one-way speed of light is c in all directions (ε = ½) and thus it cannot serve as a proof or independent measurement of that stipulation. Bridgman states,

What is the significance of this? Does it mean that there is something “absolute” about the value ½? What becomes of Einstein’s insistence that his method for setting distant clocks — that is, choosing the value ½ for ε — constituted a “definition” of distant simultaneity? It seems to me that Einstein’s remark is by no means invalidated. He was saying, in effect, that any method whatever for setting distant clocks involves an element of definition, and that in choosing the value ½ he was merely adopting a particular one of these methods (Bridgman 1962).

Thus, Bridgman notes that the conventionality thesis stands. We choose ESC (where ε = ½); we do not discover it. And this is merely one way of defining simultaneity among an infinite number of allowable choices. It is a stipulated convention and not something that can be objectively measured without first assuming it. As Bridgman puts it, “Even if the settings of distant clocks defined by the sweeping searchlight or by the clock-transport method agree in giving the value ½ for ε, nevertheless the decision to use one or the other method is a decision in our control, involving a corresponding definition of distant simultaneity” (Bridgman 1962).

The conventionality thesis was challenged in 1967 by Ellis and Bowman. They proposed a modified version of slow clock transport involving a third clock that is moved multiple times between A and B with decreasing velocities. They then extrapolate to find the zero-velocity limit of the differences between the clocks. This gives the same result as other slow clock transport methods that assume ESC. (This is because it also unwittingly assumes ESC.) Nevertheless, the authors conclude, “The thesis of the conventionality of distant simultaneity espoused particularly by Reichenbach and Grünbaum is thus either trivialized or refuted” (Ellis & Bowman 1967). But did they really establish that ε must equal ½?

Multiple authors spotted the errors in the analysis of Ellis and Bowman and published refutations of their claim. Such authors included van Fraassen (1969), Grünbaum (1969), Salmon (1969, 1976), Winnie (1970b, pp. 223–228), and Redhead (1993, pp. 111–113). As one example, van Fraassen pointed out that “Ellis and Bowman have not proved that the standard simultaneity relation is nonconventional, which it is not, but have succeeded in exhibiting some alternative conventions which also yield that simultaneity relation” (van Fraassen 1969).

Winnie (1970b, 228) pointed out that Ellis and Bowman had assumed the ESC version of the time dilation formula in their argument for ESC, thereby begging the question. Winnie states, “The basic problem with Ellis and Bowman’s proof is this: Ellis and Bowman’s proof does not avoid one-way velocity assumptions because it already assumes that ε = ½ when it appeals to the time-dilation relation (6-4) in its standard (ε = ½) form” (Winnie 1970b, emphasis added). Of course, this is exactly the same mistake Dennis made in his latest article. I feel compelled to point out that if Dennis had taken my advice in my previous refutation of his work and had actually bothered to read Winnie’s paper, he could have avoided making the same embarrassing mistake that was refuted over fifty years ago.

Winnie rightly concludes, “It is not possible that the method of slow-transport, or any other synchrony method, could, within the framework of the nonconventional ingredients of the Special Theory, result in fixing any particular value of ε to the exclusion of any other particular values” (Winnie 1970b, emphasis in original). That is, it cannot prove ESC or refute ASC.

Likewise, Salmon rightly concludes that the slow clock transport method (of the kind used by Römer) “does not constitute an independent method for ascertaining the one-way speed of light within the special theory. It shows that, whatever value we assign to ε, slow clock transport synchrony must agree with standard signal synchrony” (Salmon 1969). This is just what we demonstrated above with the New Horizons transmissions.

There have been many other papers in the technical literature on the topic of the one-way speed of light. Most of them do not involve slow clock transport. A few have attempted to overturn Einstein’s claim of the conventionality of the one-way speed of light, but all such claims have been refuted by a subsequent paper. This is because it is ultimately impossible to refute a coordinate system (which is what ASC really is).

The reason methods like slow clock transport cannot be used to objectively measure the one-way speed of light is because they tacitly depend upon the one-way speed of light in order to establish the synchronization. This has been well established in the technical literature. As Zhang notes, “It is not possible to test the one-way velocity of light because another independent method of clock synchronization has not yet been found” (Zhang 1997). He goes on to say, “What we want to stress here is that only the two-way speed, but not the one-way speed, of light has been already measured in the experimental measurements, and hence the isotropy of the one-way velocity of light is just a postulate” (Zhang 1997).

This is why the attempts of Dennis’s to use empirical observations to establish ESC over ASC cannot possibly succeed. No physical observation can refute ASC because it will always make the same observable predictions as ESC. Dennis simply hasn’t bothered to do the computations in ASC coordinates, nor is he apparently aware of past attempts to overturn the conventionality thesis and their refutations. The conventionality thesis cannot be refuted without also refuting Einstein’s Theory of Relativity because the conventionality thesis follows logically from the relativity of simultaneity as I demonstrated in my previous refutation of Dennis (Lisle 2024). Namely, an isotropic synchronization for a moving observer is necessarily a non-isotropic synchronization for a stationary observer. I am not the first to point this out (e.g., Jammer 2006). I would again suggest that Dennis read the rich body of literature available on this subject.

References

Bridgman, P. 1962. A Sophisticate’s Primer of Relativity. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Einstein, A. 1916. Relativity: The Special and General Theory, authorized translation by R.W. Lawson. New York: Crown Publishers Inc.

Grünbaum, A. 1969. Simultaneity by slow clock transport in the special theory of relativity. Philosophy of Science 36 (March): 5-43.

Jammer, M. 2006. Concepts of Simultaneity: From Antiquity to Einstein and Beyond. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lisle, J. 2018. The Physics of Einstein. Aledo, Texas: Biblical Science Institute.

Lisle, J. 2024. A refutation of Phillip Dennis’s claims regarding inconsistencies in ASC. Biblical Science Institute (July 13).

Redhead, M. 1993. The Conventionality of Simultaneity. In J. Earman, A. Janis, G. Massey, & N. Rescher (Eds.), Philosophical Problems of the Internal and External Worlds (pp. 103-128). University of Pittsburgh Press.

Salmon, W. 1969. The Conventionality of Simultaneity. Philosophy of Science (March): 44-63.

Salmon, W. 1976. Clocks and Simultaneity in Special Relativity or, Which Twin Has the Timex? In P.K. Machamer & R.G. Turnbull, Motion and Time, Space and Matter: Interrelations in the History of Philosophy and Science. Ohio State University Press.

Van Fraassen, B. 1969. Conventionality in the axiomatic foundations of the special theory of relativity. Philosophy of Science 36 (March): 64–73.

Winnie, J. 1970. Special relativity without one-way velocity assumptions: part I. Philosophy of Science 37 (March): 81-99.

Winnie, J. 1970. Special relativity without one-way velocity assumptions: part II. Philosophy of Science 37 (June): 223-238.

Zhang, Y. 1997. Special Relativity and Its Experimental Foundations. World Scientific.

[1] We stipulate the one-way speed of light in a given direction, and then this allows us to define simultaneous events that are separated by some distance.

[2] All referenced page numbers are for the first edition of the book.

[3] Proper time and the spacetime interval are basically the same thing except the signs regarding the spatial and temporal terms are reversed, and they differ by c in order to express the units in time or space, respectively.

[4] This leads to the possibility of time contraction. For example, in ASC, ε = 1, and therefore clocks moving with negative velocity (toward the observer) can tick faster than the observer’s clock.